Even in the depths of prehistory, our nomadic ancestors were moved to venerate the moon, whose presence held a profound significance in their lives. Within the dark caverns, her likeness adorned the walls, while the bones of long-extinct creatures bore the etchings of her form. Long before the advent of writing or the invention of the wheel, these ancient souls engaged in the art of lunar ritual, their silent words and forgotten songs lost to the ages.

Our ancient ancestors believed that celestial objects such as the moon, sun, and stars, as well as natural objects such as plants and rivers, possessed souls. The moon wasn’t just a bright light in the sky, but a conscious being, a deity with whom our ancient ancestors felt a sense of kinship. The honor and respect that they felt for the moon were expressed through their religion and mythology, sculptures and art, and the construction of glorious lunar temples.

The relationship that our ancient ancestors had with the moon was more than just spiritual. Understanding and tracking the cycles of the moon was necessary for survival. Our ancient ancestors used the phases of the moon to mark the passage of time, which allowed them to track the seasons. This allowed them to know when it was time to plant seeds in the spring and prepare for rain in the winter. They observed the effect the full moon had on the tides, helping them plan the best time to travel and fish. These observable natural phenomena related to the moon and her cycles, such as its association with travel and water, became characteristics attributed to the earliest lunar deities.

These characteristics, first identified by our ancient ancestors, form the basis of many contemporary mythological beliefs about the moon. Since these beliefs ultimately stem from natural observation, they feel, in a mystical sense, intuitively right. Of course, the moon holds sway over the ocean. Of course, the moon watches over travelers at night and illuminates a path forward in the darkness, both literally and spiritually. These beliefs are so ingrained, so habitual in our way of thinking that it’s easy to assume that they have always been thought of as the truth.

And in a way, they have been, mostly, but of course, not entirely. Perhaps the most prevalent characteristic about the moon is also the most contemporary: the moon’s gender.

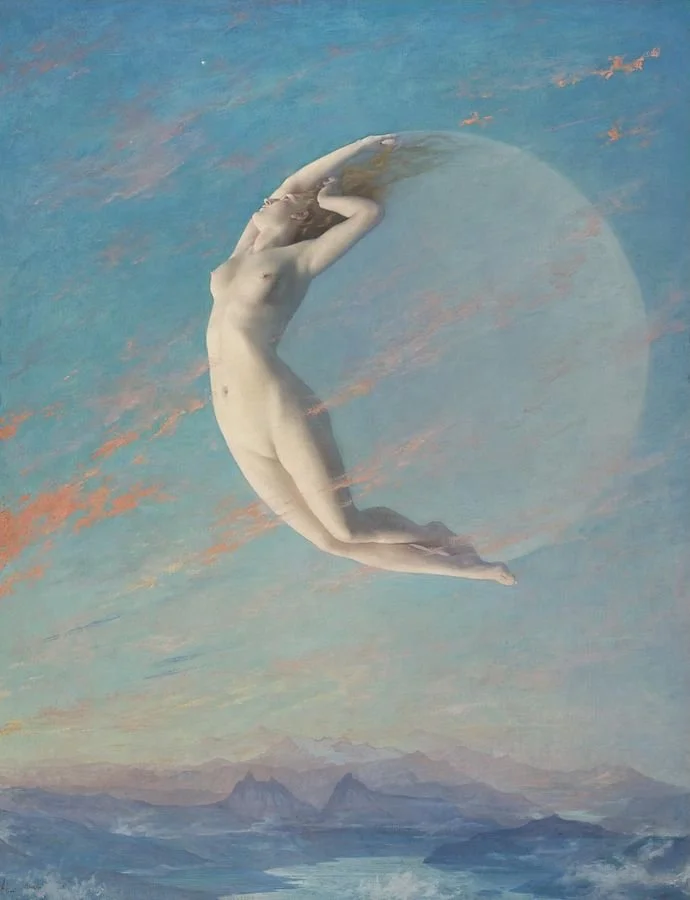

In Western culture, the moon is female. Greek authors such as Homer (presumed author of the Oddessy and the Iliad) cemented the association between the moon and femininity in their work, which went on to inspire generations of European artists, writers, and poets.

This was not always the case. Much like human gender, celestial gender is historically fluid. The world's first lunar deity is male. His name was Nanna, and he was worshiped by the Sumerians, the earliest known civilization. He continued to be worshiped, albeit by different names, by the Akkadians, and the Babylonians, remaining an important deity for over 3,000 years.

At some point in time, between the rise of the Sumerians and the writing of Homer, the perceived gender identity of the moon shifted. This is my attempt to explore and understand that shift.

Ancient Sumeria

Ancient Mesopotamia is a historic region stretching from the Persian Gulf to the Mediterranean Sea, situated between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers. Although multiple distinct groups occupied this area, it was dominated by the Sumerians and the Akkadians (and later the Babylonians) from the beginning of written history in 3100 BC to the fall of Babylon in 539 BC. Today this area corresponds with modern-day Iraq, Kuwait, Syria, and Turkey.

The Sumerians are credited with being the first civilization. One of their many achievements was the invention of the first written language known as cuneiform around 3500 BCE. This development of written language is a lens that gives us a glimpse into their religious and spiritual beliefs. Ancient Sumerian religious beliefs, and the accompanying magical practices, are therefore considered to be the world's first religion. Sumerian Gods and Goddesses were the very first ones to have their names immortalized in stone.

Very little is known about the religious and spiritual beliefs of pre-Sumerian societies. Primitive man likely practiced a form of animism, the belief that inanimate objects such as animals, plants, or natural phenomena contained a soul or spirit. Our ancient nomadic ancestors, whose continued existence relied on their ability to successfully hunt and forage, likely believed that spirit resided in the natural forces that helped or hindered their ability to thrive: trees, streams, and the weather. Over time, as small nomadic tribes grew into communities, and those communities grew into city-states, it must have become obvious that while spirit existed in both a flower and the sun, only one of those objects had a continuous and important impact on everyday life. Agriculture and commerce were the two main pursuits of human civilization at this time, and the natural forces which had the strongest continuous effect on these pursuits became the foundation of Sumerian religion.

Success in agriculture and commerce depended on auspicious climate conditions. The Euphrates Valley region had two seasons that divided the year: the rainy and the dry. During the rainy seasons, rain fell continuously for months, accompanied by thunder and lightning. The welfare of our ancient ancestors depended not only on abundant rain but also on their ability to build canals to channel water flow to avoid catastrophic flooding and irrigate their crops. Rivers were also a means of transportation, necessary for commerce and travel.

As such, it’s not surprising that the chief deity of the Sumerian people was Enlil, “the lord of storms”. In ancient writing he is also addressed as the “Great Mountain”, and his consort the goddess Ninlil was known as “the Lady of the Mountain” and was the goddess of grain. As there are no mountains in the Euphrates Valley, historians presume that Enlil was a deity of an even more ancient nomadic civilization that descended into the valley from the mountainous regions. He was also known as the “father of Sumer” and the “lord of vegetation”. These traits likely arose during his transfer from a local god of a nomadic mountainous people to the god of the inhabitants of the Euphrates Valley, which relied on his support for agriculture and cultivation. He was seen as both the creator of existence and a destructive force, reflecting the importance of favorable weather conditions for the survival of these ancient societies. Enlil was called “the king of heaven and earth” and “the father of the gods”.

We know from god lists compiled at the time, and from other writings like sacrifice tablets that the Sumerians worshiped hundreds of deities, many of which were secondary gods or personal deities. As society progressed over the roughly three thousand years that these deities were worshipped, some of these gods and deities rose to prominence, some were combined with other deities; their names adapted or changed or merged, while others faded into distant memory. As such, forming a precise genealogy of the Sumerian gods is difficult. It is however fairly well established that Enlil and Ninlil had four children, one of which was Nanna, the God of the Moon.

Nanna/Sin/Suen

Nanna, also called Sin or Suen, like his father, was a deity whose characteristics developed over thousands of years, and likely existed for centuries before the creation of writing. Historians now surmise that Nanna and Suen could have been two distinct deities, whose identities were merged during Sumerian times. In the earliest writings, the moon god is often referred to as Suen when he is described as a young man, tending to cattle herds and bringing its bounty to his parents Enlil and Ninlil. He is called Nanna in association with his relationship with his spouse, Ningal, which is often described in an erotic nature.

The Sumerian pantheon is a complex one, in which deities had characteristics unique to their own identity, as well as ones shared with other deities. Nanna/Suen is the god which was uniquely identified with the moon. The moon was considered the manifestation of his divine power and existence. The association with the moon formed the basis of his sphere of power. As such, we can assume that all of the characteristics prescribed to Nanna were also associated with the moon itself.

His name means "illumination" or "luminary”, a reference to the moon as the chief source of light in the night sky. Nanna was also deeply connected with the practice of magic: having sacred wisdom, reading omens, and practicing divination. This association is likely where the meaning of his name "luminary" comes from, for he illuminates the darkness of the unknown with his knowledge like the moon shines her light against the darkness of the night sky.

Sumerians followed a lunar calendar, and the lunar cycles were crucial to the practice of religious rituals, festivals, and holidays, and as such Nanna was also associated with timekeeping and the passage of time; he was referred to by the number 30, referencing the approximate days in a lunar month. He was celebrated each month on the first, seventh, and fifteenth day, corresponding to the lunar phases of the new moon, quarter moon, and full moon.

The journey of the moon through the night sky and its disappearance at the beginning and end of the month also took on a mystical role. The Sumerians believed that, like the moon, Nanna traveled to the underworld at the end of the month and took on a judicial role where he would render verdicts in godly disputes and decide the fates of man. The new moon was then seen as a symbol of rejuvenation and renewal when Nanna left the underworld and resumed his throne over the land of the living. The renewal of the moon every month was seen as a reflection of the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth, and as such Nanna was seen as a god who could renew and restore life for crops and animals, as well as watch over the continued existence of humankind.

Nanna was also seen as a father figure to the Sumerians, especially the inhabitants of the city of Ur, which was dedicated and sacred to Nanna. He was seen as a protector of the city and its inhabitants, responsible for their continued safety and prosperity. In this role he took on some aspects commonly associated with fertility deities, ensuring the proliferation of all things necessary for life at the time: herds of cattle, crops, fish, and even birds, as well as mankind itself. In this role as a fertility god, he is depicted riding a crescent moon (the boat of heaven) in the river, bringing water to the crops. This association with fertility also carried over into childbirth, with an ancient incantation to ease pregnancy pains stating "may this woman give birth as easily as Geme-Sin[the pregnant cow of Nanna/Sin]".

Nanna’s role relating to natural fertility and abundance is also evident in the annual harvest festival, which mimicked the tale of Nanna’s journey to Nippur to receive the blessings of his father Enlil, and return to Ur to ensure prosperity for its crops and its people. The Sumerian kings would recreate this event every year, traveling with a statute of Nanna from Ur to Nippur to present the bounty of the first harvest to the temple of Enlil, in order to ensure prosperity for the following year.

Nanna was also closely associated with cattle. The renewal of the moon each month was believed to be associated with the growth and proliferation of cattle herds. The shape of the new crescent moon in the night sky was also associated with the horns of a bull. As such Nanna was often referred to in these terms as the “frisky calf of heaven”, “the pure long-horn of heaven”, or as having “shining horns”. While Nanna’s identity was closely related to cattle, he was not the only cattle god in the Sumerian pantheon. His father Enlil was also referred to as a mighty ox or bull.

The association of the bull with multiple deities was not an issue for the Sumerians, rather simply the many characteristics of the bull could be compared to the attributes of different deities. The bull was associated with military power, authority, strength, and violent storms, as well as agricultural and sexual fertility. Many of these characteristics also overlapped, with one hymn describing Nanna as a:

“proud bull calf with which horns and perfect proportions, with a lapis beard, bull of virility and abundance”

Nanna’s consort was the goddess Ningal, and together they had three or four children. One of these children was Utu, the Sumerian god of the sun.

This belief that the moon gave birth to the sun seems counterintuitive to a contemporary worldview. Clearly, the sun is the greater of the two celestial objects, both in size and in relevance to our everyday lives. However foreign to our understanding of the world this belief may seem, it demonstrates the importance that the ancient Sumerians placed upon the moon in their lives. Not just their spiritual and religious lives, but their actual survival as a civilization.

The honor and importance that the Sumerians placed upon the moon is also evident from the fact that Nanna/Sin was considered to be an important deity. He was the patron God of the city of Ur, the location of his main temple where he was worshiped for thousands of years by the Sumerians, Akkadians, and Babylonians. Between the beginning of the Akkadian until the middle of the Old Babylonian period, the daughter of the reigning king was appointed as the High Priestess of the moon temple at Ur.

One possibility as to why the ancient Sumerians thought the moon gave birth to the sun could be that this belief is a continuation of an even older spiritual belief system from before the first agricultural revolution (the beliefs held by the ancient ancestors of the ancient Sumerians). In hunting-gathering societies, the moon played an incredibly crucial role in survival. It allowed our ancient ancestors to track traveling herds of animals at night, mark the passage of time, and predict tides. This reliance on the moon for survival could explain the importance that ancient civilizations placed upon it. It could also explain why the moon was assigned the masculine gender, as ancient cultures are believed to have been patriarchal and thus would have prescribed the more “desired” gender to what they perceived to be the most important celestial object.

Ancient Egypt

Unlike the ancient Greek pantheon which was based on a familial hierarchy, the Ancient Egyptian deities had more complex personalities and multiple functions. As such many different deities were associated with the moon through their mythology.

While there is no single moon god, the lunar deity that was considered the personification of the moon was Khonsu. His name means movement or traveler, and like Nanna, he also marks the passage of time. Like the Sumerians, the Ancient Egyptians saw the cycles of the moon, its eternal rise and fall through the sky as a representation of transformation, rejuvenation, and eternal life, and Khonsu was often depicted as being eternally youthful, or as a young man who ages but is regularly reborn.

While Khonsu is the personification of the moon itself, Thoth is one of the most important and prominent Egyptian lunar deities. He and the sun god, Ra, are called "the two followers" in the sky. Thoth was also known as "the silver disk", in reference to the moon itself. Like Nanna, Thoth is the god of writing, wisdom, science, magic, and ritual, as well as keeping the religious calendar.

For both the Sumerians and the Ancient Egyptians, the moon represented the passage or measuring of time, as well as being a keeper of hidden occult knowledge. But unlike the Sumerians who consolidated these roles under one deity, the Ancient Egyptians assigned guardianship over these roles to multiple Gods.

Curiously, both the Ancient Sumerians and Egyptians associated bulls and cows with fertility and childbirth, and both cultures associated those animals with the moon. Egyptian lunar gods were referred to as having "sharp horns". Ancient Egyptians also colloquially referred to the crescent moon as the "rutting bull" and the waning moon as "an ox". There is an interesting parallel in that the masculine Sumerian God Nanna was associated with cows, fertility, and the moon while female Egyptian deities are associated with cows, fertility, and the sun. Goddesses associated with fertility such as Hathor and Isis were both depicted with cow horns and sun disks above their heads.

The shift in gender could be for practical reasons. As women are the ones who give birth, it seems natural that there would be a need for their own female deity to protect them during labor. The Egyptian fertility goddess’s association with the sun could be simply a result of the difference between the Sumerian and the Egyptians’ attitudes toward the moon. Unlike the Sumerians, the ancient Egyptians believed that the sun was the most important celestial object. This is indicated in their mythology and the fact that all of the most important deities, as well as the deities of creation, such as Ra and Amun, are all solar. Perhaps they thought that the act of bringing forth a new life into existence was more akin to the role that the sun played in their society.

Although there are many similarities between the ancient Sumerian and Egyptian beliefs about the moon and lunar worship, it is difficult to say how much Egyptian religion and mythology was actually influenced by the Sumerians. There is abundant evidence that these two ancient civilizations were in communication with each other. Examples of early influences between the two cultures can be found in the form of similarities in their art, pottery, and architecture (including the construction of step pyramids). A series of famous correspondences between the two nations known as the Amara Letters clearly demonstrates that the Sumerians and Egyptians interacted with each other as allies and trading partners. Certainly, there was ample opportunity for the ancient Egyptians to be inspired and influenced by Sumerian religious and spiritual traditions, and vice versa.

The similarities between these two cultural beliefs about the moon are impossible to ignore. Both cultures associated the moon with water, timekeeping, the cycle of life/death/rebirth, magic, mysticism, and hidden knowledge. These similarities may be the result of Sumerian influence on Egyptian culture, or, they can serve as an example of how different cultures interpreted natural phenomena in a similar way.

Ancient Greece

The most well-known lunar deity today is the ancient Greek and Roman goddess Selene/Luna. However, the worship of male lunar deities didn’t fade away with the ancient Egyptian empire. Male lunar deities continued to be worshiped during the Greek classical antiquity period (between 8th and 6th centuries).

The Phrygians (from Phrygia, an ancient kingdom in what is now part of Turkey) worshiped a lunar god called Men. He is depicted with horns protruding from his shoulders, and he also presides over the passage of time. The Phrygians are considered closely related to the Greeks and are often mentioned in Greek mythology such as the tale of the Phrygian King Midas, whose touch turns objects into gold.

Another example comes from the ancient Turkish city called Harran. Over 4,000 years ago the Sumerians establish a temple there to honor their moon god Nana. It was known as "The House of Rejoicing" and while it was not as important as the primary Nanna temple in Ur, it was a sacred location in its own right.

Later during the Neo Babylonian period, King Nabonidus, who ruled between 556-539 BCE expanded this temple, making it a famous center for the study of astronomy and divination, and the worship of the moon god Nanna who was then known by his Akkadian name Sin.

This city continued to be inhabited and well known in Roman times where it was called Carrhae. But what of the House of the Rejoicing? Did the worship of the moon god continue?

The answer to this question comes from an unlikely source. Among the many manuscripts stored in the Vatican Library is a collection of the biographies of Roman emperors called — the Vitae Diversorum Principum et Tyrannorum a Divo Hadriano usque ad Numerianum Diversis compositae, or as its more commonly known the Historia Augusta. One of the emperors included is Antoninus Caracalla, who ruled from 198 to 217. The author describes the life of Caracalla, but it is his death that is relevant. The author describes how while passing through Carrhae, Caracalla paused at a temple to worship the god Lunas, stepped outside to relieve himself, and was murdered by the prefect of the guard. Apparently, Caracalla was not all that well liked during his lifetime. In any case, the author takes this opportunity to provide some additional commentary, as follows:

"Now since we have made mention of the god Lunus, it should be known that all the most learned men have handed down the tradition, and it is at this day so held, particularly by the people of Carrhae, that whoever believes that this deity should be called Luna, with the name and sex of a woman, is subject to women and always their slave; whereas he who believes that the god is a male dominates his wife and is not caught by any woman's wiles. Hence the Greeks and, for that matter, the Egyptians, though they speak of Luna as a "god" in the same way as they include woman in "Man," nevertheless in their mystic rites use the masculine "Lunus."

David Magie, who translated this work into English, points out that the god referred to in this passage as Lunus was in fact the Sumerian moon god Sin, who was worshipped at Carrhae at the time, and who was depicted on the coins of the city. Magie suggests that Caracalla was likely ignorant to this fact and could have thought that the temple was one dedicated to the goddess Selene.

This evidence demonstrates that the worship of male lunar deities didn’t abruptly fade away in ancient Greek times. The worship of male lunar deities and the ancient symbolism associated with the moon in Sumerian times continued to remain popular and changed with the times to adapt into this new age.

Greco-Roman Lunar Worship

Although the worship of male lunar deities stretched all the way from the time of the ancient Sumerians in 3500 BCE through well into the Roman empire, it is the mythology and religion of the Ancient Greeks that formed the foundation of contemporary moon symbolism.

Greco-Roman lunar deities are similar in many ways to their more ancient Sumerian and Egyptian counterparts. In all three cultures, the moon symbolizes fertility and childbirth, secret and hidden occult knowledge, the arts of magic and divination, as well as the passage of time. The most obvious difference between the beliefs of the Greco-Roman and their predecessors was the gender identity of the moon. Additionally, while the Sumerian Nanna subsumed all of the broad traits and characteristics associated with the moon under his sole control, Greco-Roman mythology assigns each group of traits to its own deity. The deities most closely associated with the moon are the Goddesses Luna, Artemis, and Hecate.

Selene, also called Mene or Luna, was the goddess that personified the moon. She is described as a beautiful woman with long wings who rides a horse-drawn chariot across the sky. She is associated with beauty, and is depicted in art wearing a long gown or robe, with a crescent moon above her head. She is also associated with deep romantic love and longing epitomized by her relationship with her love, the mortal shepherd Endymion who is placed into an endless ageless sleep so they could be together always.

Like the ancient Sumerians and Egyptians, the ancient Greeks also measured time in moon cycles and used them to plan their rituals, festivals, and religious ceremonies. Being the goddess of the Moon, Selene was also associated with the passage of time, her children being the Menai (Menae, Months), and the four Horai (Horae, Seasons).

Artemis is a lunar goddess of the hunt, and wild spaces. She is a protector goddess, watching over women in childbirth, and protecting virginity and young women. She was typically depicted as a young woman herself with a silver hunting bow and a quiver of arrows. Her Roman equivalent is Diana.

Artemis is always depicted as a young girl or maiden, pure and chaste. She never marries, remaining forever a virgin. As such, Priests and Priestesses that were devoted to her were also expected to abstain from sexual activity. Artemis was known to be a fierce protector of young women and their modesty. One tale describes how she kills Actaeon, a hunter who watches her bathing by transforming him into a stag and sending her hounds to tear him to pieces. Through Artemis, the Moon continues to retain its association with fertility and childbirth.

Her association with wild animals was twofold. On one hand, she was the Goddess of the Hunt and associated with killing game and a successful hunt, while on the other hand, she was also the protector of animals. She was often depicted riding a chariot with a wild stag or hunting dogs.

The way that Artemis was perceived and her worship varied greatly depending on the location and time period. However, she was always portrayed in some way as the goddess of wild and untamed nature, and she was often accompanied by nymphs, with whom she venerated nature with her dancing. As such, Artemis instilled an even deeper connection between the Moon and nature, especially wild and untamed places.

The exact origins of Hecate are unknown, but some researchers believe that she began as an aspect of the goddess Artemis. Artemis initially was associated with both "light" attributes like maidenhood and purity as well as "dark" attributes like magic and communicating with the souls of the dead. Overtime Artemis became more closely associated with her light attributes, while her darker attributes were personified under a new goddess, Hecate.

Like Nanna and Thoth, Hecate is associated with the moon, witchcraft, divination, and knowledge of sacred and poisonous plants. Like Thoth, Hecate is associated with the underworld, death, and ghosts. In the famous story of Persephone, Hecate guides Demeter through the underworld carrying flaming torches and stays with her once she is found to be a companion and guide.

Hecate is deeply associated with travel and protecting the traveler. She is the goddess of the crossroads. In the 1st century AD, Ovid wrote: "Look at Hecate, standing guard at the crossroads, one face looking in each direction." Many of her shrines were placed at crossroads, where she was worshiped by travelers seeking her protection.

The original representations of Hecate are of her singular form, depicted on vases as a woman holding two torches. As she evolved, she was depicted in her sculptures in triple bodied form, and eventually as a goddess with one body and three faces. Hecate is considered by some to be the original triple moon goddess, her other aspects being Artemis and Selene.

The Moon as Female

As the Roman empire expanded throughout Europe, it also carried with it and spread its beliefs, traditions, and mythology resulting in the proliferation of these beliefs throughout the continent. With the rise in Christianity, many of these myths and stories temporarily faded from the collective attention of mankind until they were rediscovered during the European Renaissance of the 15th and 16th centuries. During this time the poetry of Ovid and Homer became a major influence on artists resulting in some of the most famous works of art like Botticelli's The Birth of Venus and Leda and the Swan by Leonardo DaVinci. Poets and writers like Dante and Shakespeare were also inspired by and incorporated Greek and Roman mythology into their work.

During the European Enlightenment in the 18th century the cultural focus shifted to celebrating the ancient Greeks for their more scientific and philosophical achievements, but the fascination with their religion and mythology never fully abated, coming into bloom again during the Romanticism movement. Many of Homer's works were translated into English, which in turn inspired a whole new era of contemporary poetry, writers, and artists.

Longfellow describes her as an Empress and a phantom, both serene and proud, and full of pain. To Shelley, she is a dying lady, thin, pale, and insane. To Lady Mary Wortley Montagu she is many things, a guardian of love and a source of inspiration, as well as a friend and a goddess. While none of these famous poets could agree about her characteristics, for all of them the moon was a woman.

Linguistics

One lens through which to view the shifting gender of the moon is through linguistics, the study of language. The cultural change in perception regarding the gender identity of the moon was profound and widespread enough to cause a change in the written language around the time of the writing of Homer. Not only did lunar deities become female, but the word for "moon" itself changed from being a male word meaning "to measure" to a female word meaning "to shine".

Proto-Indo-European (PIE) is a language that linguists theorize is the common ancestor for the Indo-European language family, a language family native to western and southern Eurasia. While no direct record of Proto-Indo-European exists, more work has gone into reconstructing this language than any other proto-language. It is theorized that PIE was spoken as a single language from around 4500 BC to 2500 BC. As civilization evolved, our ancient ancestors began to travel, migrating throughout Europe and as far to the east as India. As a result of this migration, they became more isolated from each other, leading to regional dialects, which over hundreds of years transformed into the Indo-European language, and finally, into the modern languages people speak today. The reconstruction of PIE has given historians insight into some of the cultures and religions of our ancient ancestors.

The Indo-European word for "moon" is reconstructed as *meh1n(e)s. The root of this word is "meh1" which means "to measure" and the ending "n(e)s" refers to an action, a literal translation being "one who measures" or "measurer of time". Since PIE languages did not conjugate their words based on gender, the most literal translation is "he/she/one who measures time". As our ancient ancestors measured time based on phases of the moon, this word also came to mean "month".

When Indo-European evolved into Latin, the word for moon evolved to "men", a masculine conjugation of the root "me" meaning to measure, which was also used in "mensis" meaning month and "menstruus" meaning monthly, as well as "mensura" meaning measuring. This makes sense because the moon was still closely associated with measuring the passage of time.

However, around the time of the 8th or 9th century BC, an interesting change occurs. In both Greek and Latin, the word "moon" was replaced. The old word for the moon "men" whose root means to measure and has a masculine conjugation was replaced with "selene" a Greek word that means "blaze of flame" and the Latin "luna" meaning light or illumination. This shift must have already been happening during the time of the writings of Homer who twice referred to the moon as "mene" which is the feminine form of "men". This could represent a transitional moment, where the moon was already perceived by the general population to be female, but the language had not yet finished evolving.

It is impossible to say exactly why this change to the language occurred. We do know that there was a Proto-European parallel word for moon, "louks-na" meaning "light" or "to shine", from which the Latin "luna" evolved. But the existence of a parallel or alternative word still does not explain the overall cultural shift.

In theory, language evolves as culture evolves, so a cultural shift must have occurred regarding the common person's understanding and beliefs about the gender of the moon, although we don't know when or why exactly this shift occurred or why. Interestingly, this change didn't occur only in Greece. The Old High Germanic word for moon maintains the root meaning to measure but conjugates into the female gender.

This linguistic change cemented the classical western understanding of the moon as a female entity and continued to pass this idea on through the romance languages that evolved from Latin and have gendered nouns, like Italian, Spanish, French, and Portuguese, where in each case the word "moon" is female. Even in places like the United States, the moon is culturally associated with the female gender, even though linguistically the English language does not have gendered nouns.

More thoughts on the shift

A few different factors could have played a role in the evolution of the moon's gender identity. First, over thousands of years of human evolution, observation of the moon and its phases went from being necessary for the survival of each individual to something that is mostly practiced purely for religious and spiritual purposes. Religious functions were performed by Priests and those in the upper echelons of society. For the average person living in ancient Greece, the importance of the moon to daily life decreased. Perhaps as the relative importance of the moon decreased, so did its need to be associated with the dominant gender.

Or, perhaps, the association of the moon with the female gender was a natural continuation of the observation of nature and natural phenomenon. Since ancient Sumner, the moon has been associated with the biological functions of womanhood, fertility and childbirth. A woman’s menstrual cycle and the cycle of the moon are both about roughly the same length. These two things, womanhood and the moon, perhaps were seen as similar enough to be related. Women also took on the other roles associated with the moon, including the practice of magical arts. The oracles of Greece and the sibyls of Rome were women, with Oracle Priestess at Delphi being one of the highest authorities on both civil and religious matters.

Second, solar calendars while already in use by the ancient Egyptians were developed further and made more accurate by the Romans. The word for the moon literally meant to measure time, and with this change the moon lost its primary function. Could this be what created the vacuum that precipitated the shift? Finally, perhaps the Greeks or Romans were inspired or influenced by another culture that they encountered that already had female lunar deities.

Evolution of Timekeeping

Timekeeping was crucial for the survival of our ancient ancestors. It was important to understand celestial alignments so that they could plan when to plant their crops in the spring and harvest them in the summer, predict when the weather would become rainy and prepare for potential snow or river flooding.

The earliest calendars are lunar and date back to 32,000 BCE. These calendars were made up of straight or crescent-shaped lines carved into animal bones. The sets of marks were often represented in a serpentine pattern, suggesting an association with snakes or rivers. A lunar calendar is also depicted in the famous Lascaux caves in France. These caves are the location of some of the earliest cave paintings in existence, depicting over 600 images of animals and people and are estimated to be 15,000 years old. The association between the moon and measuring or marking the passage of time was already ancient by the time that cuneiform was invented.

The earliest Sumerian calendar discovered to date is the Umma calendar from the late centuries of the third millennium BCE. It is a lunisolar calendar, meaning that it was based on both the moon and the sun. The day was based on the rising and setting of the sun, the month was based on the moon cycle, and the year was based on the changes in the sun's rising and setting location and position throughout the year. This was a primitive calendar that still relied heavily on the moon, and the observation of moon phases which were also very important for Sumerian religious worship, rituals, and divination.

The Ancient Egyptians had two calendars: a lunar calendar for religious rites and ceremonies which was used exclusively until a civil solar calendar was introduced around 2500 BCE. Unfortunately, the solar calendar didn’t account for leap years and as a result, it lost about one day every four years. Attempts to fix this discrepancy eventually led to the creation of the Alexandrian or Coptic calendar by Augustus, which became the official calendar of Egypt in 25 BC. This calendar was primarily used by the Coptic Orthodox Church and the farming people in ancient Egypt. The Julian calendar, a solar calendar, was proposed by Julius Caesar and became the official calendar in 45 BC and the predominant calendar used throughout the world until it was slightly adapted one final time by Pope Gregory XIII in 1582, after which it became known as the Gregorian calendar that we still use today.

During the time that Homer and Hesiod were writing their epic tales, the solar calendar had already been in existence for a long time. In earlier times, the moon had a very specific practical function: to mark the passage of time. With the invention and proliferation of the solar calendar, the moon quite literally lost its primary function. Perhaps this created an opportunity, an opening, to recast the moon in a role that was more befitting with the evolving cultural and spiritual norms of the time. Of course, this new role for the moon was not entirely new. The moon had already been associated with fertility, travel, and magic for thousands of years, and this new shift simply elevated those aspects of moon worship to the forefront.

CONCLUSION

The moon was worshiped as a male lunar deity continuously for around 4000 years. Not only that but the moon, as a symbol, has represented the same qualities continuously throughout that time. The shift in gender happened gradually but thoroughly. It permeated every aspect of ancient life including its mythology, religion, and even its language. This shift was so fundamental to our human understanding of the world that today it feels almost intuitive. It feels as authentically true as something that is naturally observed. Of course, the moon is female. Of course.

(Bibliography incoming shortly)